A few days ago, on a lightning strike, the media circulated news of the CJEU judgment in the ‘CBD case’. From what I have noticed, most of the publications on the subject were limited to the content of the judgment. However, I did not find any analysis resulting in a commentary on the consequences of the judgment. So I have drawn up a few words of reflection on the potential impact of the judgment on the future of the hemp industry in Europe.

The industry, understandably, was very optimistic about the judgment. In my opinion, however, the verdict itself is not surprising or revolutionary.

The court found that the French legislation prohibiting the extraction of CBD from flowers and fruit is contrary to European freedom of movement of goods.

This should not come as a surprise, as the French restrictions preventing the extraction of the richest cannabinoid parts of the plant did not have any rational justification (especially when confronted with the argument that synthetic CBD does not face any such obstacles) and were therefore untenable. The first obvious and direct result of the resolution should be to open the French market to certain CBD products.

However, what should have a greater impact on the market is the issue being considered by the court a little bit on a side and leading to the conclusion that CBD is not a narcotic. Moreover (point 72) the CBD ‘has no psychotropic effects as well as there is no scientific data to establish its harmful effects on human health’.

Borat would say: ‘great success‘, young people would say: ‘well done Captain obvious‘, but… confess!

Who of you you did not know that?

This has been clear to the cannabis community for a long time, and the only ones to be ‘surprised’ are the European Commission. Weren’t there doubts about the ‘narcotic‘ status of the CBD that caused the European Commission (‘’EC’’) to stop proceeding the applications for Novel Food?

Therefore, the most important effect of the ruling should be to resume the work of the EC, but, as we know, this will not happen until December, when the UN Committee on Drugs will move hemp from Schedule IV. That is what surprises me the most.

Can’t Europe afford its own drug policy?

Does the EU really need to look at a country (which almost re-elected Trump as a President) which, based on a lie, declared war on Cannabis for racist, xenophobic and anti-pacific reasons, to then allow recreational use of Cannabis in around 15 states, and medical use in around 35 of them?

After all, the EU has the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction established on the basis of Regulation (EC) No 1920/2006 the aim of which is to provide the EU institutions and Member States with objective, reliable and comparable information on drugs and drug addiction and to offer policymakers the data they need to draw up well-thought-out drug laws and strategies.

Certain helplessness of the Court is shown by the fact that, in order to come to the conclusion that the CBD is not a narcotic, the CJEU had to use the purposeful interpretation of the Single Convention because in the Court’s opinion, a linguistic interpretation could lead to different conclusions?! (point 71).

I must admit that I am missing out on the Court’s reasoning. If the substances included in the Schedule are narcotics (by the way, a specific way of defining, since the Convention does not define the common characteristics of a collection of narcotic substances, e.g. impact on the central nervous system causing a disturbance in the perception of reality), and the Schedule includes Cannabis and Cannabis resin, it should be clear that cannabidiol (CBD) is not a narcotic and there is no need to refer to a purposeful interpretation. It is clear already on the semantic ground that the wheel of a car is not a car, as well as that cannabidiol is not Cannabis.

In addition, the fact that the CJEU’s decision is based on the Single Convention is questionable and objectionable in general. The Act of 1961 (when the endocannabinoid system was discovered and described in the 1990s) is archaic and completely out of line with the present state of science and knowledge. Firstly, The Convention, unlike European legislation, does not in principle distinguish between fibrous and other cannabis, and all cannabis is thrown into one bag of cannabis indica.

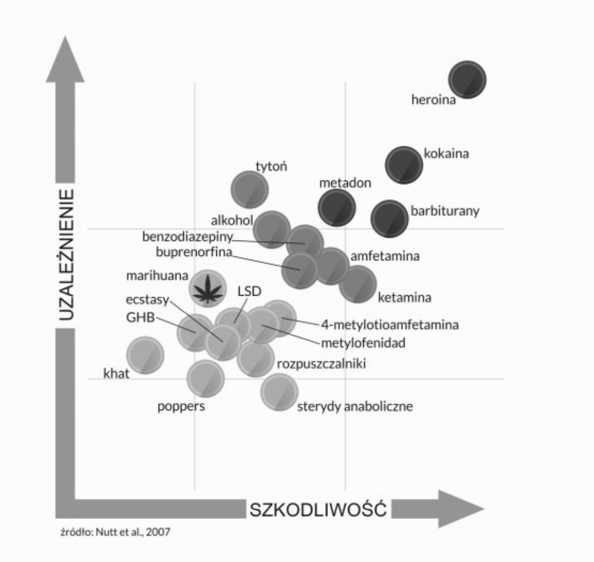

Secondly, it includes Cannabis in Schedule IV as a particularly dangerous narcotic with no therapeutic advantage. With some luck Cannabis will be reclassified later this year. However, if you are aware that the prohibition of Cannabis, sanctioned by the Convention despite the lack of scientific evidence of its harmfulness, with the evidence of its medical functions at the same time, is the result of racist and xenophobic prejudice, then basing the European judgment in 2020 on the text of the Convention from 1961 is at least debatable.

I think it is time for a coherent, evidence-based, uniform European policy on hemp. A young market is already developing and will seek professionalisation, but for this to happen, a number of real problems need to be resolved.

0.2% of THC – does it concern a plant or also the products made from it?

Observation of products available on the market forces us to reflect on (apparently obvious issue), whether the 0.2% THC level applies to the plant and is intended to distinguish between fibrous hemp and others, or whether it also applies to the products?

This problem itself was not directly addressed in the ruling, but the French State had no doubt about it, indicating that (point 27) ‘the 0.2% THC content applies to the hemp plant and not to the finished product that comes from it’.

CJEU slipped through the problem by stating that (paragraph 31) ‘the level of THC present in the products tested was always below the legal threshold‘.

What threshold? Is there a level of ‘permitted THC concentration’ in the product that is the subject of the ruling, namely the e-cigarette cartridge? From another point in the judgment (paragraph 55), it can be assumed that THC ‘was at the contamination level’. I think that such legal uncertainty (especially of the legal area at the borderline between criminal, pharmaceutical and commercial regulations) is not helpful to entrepreneurs.

I’m now coming back to the question about the actual effect of the ruling, i.e.what will change? How will it affect the market?

Currently, entrepreneurs are facing a significant problem. It is not a secret that a plant grown in natural (outdoor) conditions may have different concentrations of cannabinoids depending on a number of variable external factors (including weather). Up to 0.2% THC level, everything is okay. Growing, sale and distribution of drought not exceeding this limit is allowed. However, if it happens that the THC concentration exceeds this magic and artificial ceiling, the entrepreneur turns into a dealer who puts the drug on the market. In addition to criminal charges, he is also threatened with forfeiture of his crops. The European Parliament seems to be aware of this problem, but the recent agreement on the position to raise the limit to 0.3% THC within the framework of the common agricultural policy will most likely do little to help farmers and entrepreneurs.

It would therefore be appropriate to postulate that the 1% THC limit should be allowed.

Restriction of the free movement of goods

Following the reasoning of the CJEU, given that a number of Member States have decided to appoint higher limit (e.g. Italy with 0.6% limit), shouldn’t we treat national provisions setting a concentration limit of 0.2% as a measure having equivalent effect to quantitative restrictions within the meaning of 34 TFEU (if it prevents the access to market of one Member State for products coming from other Member States)? (point 81) After all, as the CJEU concludes, a national rule should be appropriate to guarantee the objective pursued and should not go beyond what is necessary to achieve it. How will a Member State argue that precisely the 0.2% THC level is necessary, and not for example 0.5?